Cardiac rehabilitation: impact and concept (English)

Release date: 2016-09-09

An overview of the evidence for cardiac rehabilitation, including the core components of cardiac rehabilitation, its impact on morbidity and mortality and the need to improve uptake.

The health landscape is continually changing. Financial austerity has reached peak levels and led to demands from health funders and commissioners for much greater accountability in terms of the quality of service delivery and measurable patient outcomes.

Cardiac rehabilitation (CR) is a clinical and cost-effective intervention delivered by a multidisciplinary team (MDT). Despite having extensive evidence of effect, it has failed to attract half of eligible patients. 1-3

4,5 Cardiologists play a fundamental role in treating heart disease, a heart attack, with GPs orchestrating the longer-term care of these patients.

Cardiologists and GPs are well placed to support and endorse CR by promoting referral, which is known to improve uptake and completion of CR.

What is cardiac rehabilitation?

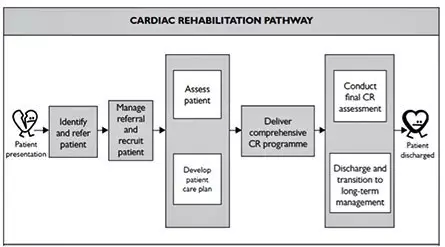

Cardiac rehabilitation often involves a combination of inpatient and outpatient services. Patients are recruited during an acute cardiac event or planned hospital procedure and supports them through to baseline assessment, core delivery of CR, and final re-assessment with long-term planning (Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

CR services are multi-component, tailored to patient need, and based on an assessment of all core components of CR, which includes lifestyle interventions, education, risk factor management, psychosocial interventions, and long-term management, delivered by a skilled multidisciplinary team (see box 1). 6

| Box 1: BACPR core components of cardiac rehabilitation 6 | |

|---|---|

Lifestyle interventions for:

Education and support for health behaviour change | |

How do we know about the quality of CR delivery?

The National Audit of Cardiac Rehabilitation (NACR), which is funded by the British Heart Foundation, monitors CR delivery against nationally agreed minimum clinical standards. 1

The NACR tracks uptake to CR annually and, although there has been a steady improvement year-on-year, the national mean for CR uptake remains at less than half (47%) of the number of eligible patients. 1 Repeated NICE guidance, over The last 10 years, has recommended CR attendance for conventional post-heart attack patients, and those with heart failure. 3,7

Delivery

A recent review of CR evidence and practice highlights that UK CR has made significant progress but programmes need to be more innovative if they are to attract a higher proportion of eligible patients. 8 The British Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation (BACPR) service standards for CR, and national data from routine clinical practice, suggest that patient outcome is optimal when CR is delivered early. 6,9

There is huge variability in the timing of CR across England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, which is major concern as it means that patients in one part of the country, where CR is timely, are likely to do better than in locations where there Is a significant delay in starting CR. 1

The traditional mode of delivery is predominately structured, group-based programmes which can be effective if delivered to evidence-based protocols. However, many patients are not attracted to this mode of delivery, with some preferring home-based or self-managed CR.

The cost for delivery and outcomes from hospital-based and facilitated home-based CR are comparable. 10 Aligning the mode of delivery of CR with patient choice not only helps to resolve issues about low uptake but is also known to yield comparable benefits to group- Based CR. 11 Patients should be offered a range of options, including group-based, home-based, and even online CR, all of which can be supported by conventional CR teams.

The caveat to this type of innovation is that patients will require a thorough baseline assessment and it is essential, as part of the CR approach, that patients are invited back to undergo a post-CR assessment. Without pre- and post-CR assessments, Providers are unlikely to develop the evidence to support patient choice and preference.

Effects of cardiac rehabilitation

Effect on mortality and morbidity

Two updated Cochrane reviews have established the strength of evidence underpinning CR. The first, by Anderson and colleagues, involved 63 studies with 14,486 participants, and found that CR reduced cardiovascular mortality (relative risk [RR] 0.74,), and the risk of hospital Admissions (RR 0.82). There were additional benefits in the form of higher levels of health-related quality of life after CR. 2

The second was by Taylor and colleagues, and involved 33 trials with 4740 heart failure patients. There was a trend towards a reduction in mortality with longer follow-up (more than 12 months), RR 0.88. Heart failure specific admissions were significantly reduced ( RR 0.61), and there was improvement in health related quality of life (HRQL). 12

What is clear from the literature is that multi-component CR is effective, and that the exercise component is safe.

Cost-effectiveness

Compared to other cardiology interventions, CR is neither costly nor difficult to provide. Based on NACR data, CR core delivery in hospital, community, or home settings (assuming an 8-week minimum period with twice-weekly sessions), costs around £600 Per patient. NICE guidance has established the cost-effectiveness of CR. 3

In addition, CR is value for money with an estimated cost per life-year-gained of £1957, which is half of of elective percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and is only surpassed by aspirin and beta-blockers for secondary prevention, with a Cost of less than £1000 per life-year-gained. 13

Participation

Although many CR programmes have evolved to take a wide range of patients, the evidence base that defines in-scope patient groups is relatively clear about who benefits from CR. NICE guidance clearly recommends CR as a key part of the management of acute coronary syndrome ( Including unstable angina and non ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction [NSTEMI]) and heart failure. 3,7,14

The most recent review of stable angina management (CG126) concluded that lifestyle change, and symptom and risk factor management were important aspects in the management of angina. However, the NICE review panel were unable to recommend CR based on too few quality trials. 15

Participation targets

The NHS England Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) Outcomes Strategy has set an ambition to increase uptake to CR from 45% to 65% in patients with coronary heart disease (CHD), and to 33% in patients with heart failure. 5

Recent analysis from the BHF research group established that CR outcome is not determined by volume of patients seen per year, which means that the challenge of low uptake rates can be met by both local and central initiatives. 16

Who takes part?

The 2015 National Audit for Cardiac Rehabilitation (NACR) annual report showed that 47% of all eligible patients attended CR, with variation across the four classic conditions from 38% for MI patients to 59% for bypass patients. 1

Data on heart failure is limited due to national coding variations in reporting heart failure patient numbers. Since the release of NICE guidance on heart failure7 91% of CR programmes in the UK now offer CR to patients with HF.

Modern approach to commissioning and accountability

In order to reduce the variation in CR delivery and outcomes identified by the NACR, the BACPR developed national minimum service standards (box 2) and core components of CR which were updated in 2012. 1

To help encourage the use of the national minimum standards, the BACPR and the NACR have implemented a programme to certify whether CR programmes meet these standards.

The National Certification Programme (NCP) uses BACPR registration paperwork and routinely generated data from the NACR to assess each application. The aim is to ensure that all programmes achieve a basic minimum standard, and to assist programmes in achieving high quality delivery and outcomes. The first 6 months, 14 programmes applied, with 12 securing immediate certification and two others referred with minor changes requested in the next 6 months. Over 50 additional CR programmes have now expressed an interest in applying for certification.

| Box 2: BAPCR minimum standards | |

|---|---|

| |

The major challenges facing CR

For the most part, CR is equitable in terms of uptake from the different diagnostic treatment groups. However, there are too few women and fewer older patients (more than 70 years old) than expected, based on acute cardiology eligibility. Coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) wait times, more than 50%of patients are waiting too long and we know delays can lessen the benefits.

A tailored intervention, underpinned by assessment, is a national minimum standard, yet around 25% of programmes fail to carry out an assessment prior to starting CR, and around half of all programmes that carry out a baseline assessment fail to re-assess after the CR core intervention.

In terms of the duration of core CR, 75% of programmes are delivering CR at or above the guideline for duration. However, 10% of programmes are for a duration of less than 5 weeks. There is no new funding on offer and there are Emerging numbers of patients to manage, which means that greater innovation and efficiencies are required if programmes are to meet NHS service and patient demand.

Next steps for CR

There is a drive to fully implement the BACPR-NACR certification programme and to use key service indicators, developed with the NHS and NICE, to implement best practice for CR. We are working closely with patients and groups through the Cardiovascular Care Partnership UK to implement An online map to help support patient choice.

The BHF Research Group, the NACR, and the BACPR are working collectively to establish which factors determines high performance in CR delivery and outcome, and to produce models and evidence to support their implementation in routine clinical practice.

Professor Patrick Doherty, Chair in cardiovascular health, Director of the National Audit of Cardiac Rehabilitation, Deputy head of department (Research, British Heart Foundation Care and Education Research Group, University of York, York, United Kingdom

Professor Gill Furze, Lead for the Cardiac Rehabilitation, National Certification Programme, Centre for Technology Enabled, Health Research, Coventry University, Coventry, United Kingdom

Source: Network

The electric wheelchair is based on the traditional Manual Wheelchair, superimposed high-performance power drive device, intelligent operating device, battery and other components, transformed and upgraded.

A new generation of intelligent wheelchairs equipped with artificially operated intelligent controllers that can drive the wheelchair to complete forward, backward, steering, standing, lying, and other functions. It is a high-tech combination of modern precision machinery, intelligent numerical control, engineering mechanics and other fields. Technology Products

Wheelchair,power wheel chair,surgical equipment,medical equipment

Shanghai Rocatti Biotechnology Co.,Ltd , https://www.shljdmedical.com